A few weeks ago, I shared that my dual enrollment students' high school GPA was the strongest predictor of college success — stronger even than scores on college placement exams. Last week, it struck me that half the group of students we sent (our juniors) were taught in 100% New Tech courses before dual enrolling in college. The other half were seniors who were taught in traditional classes one year ahead of our New Tech initiative. What a great opportunity for data comparison!

For those unfamiliar with New Tech, let me explain:

Three years ago, my district contracted with the New Tech Network to support change in our high school in three key areas:

- Empowering students through increased voice and choice in their learning.

- Engaging students in deeper learning of course content through wall-to-wall implementation of project- and problem-based learning as our instructional model.

- Enabling students to foster their own learning by providing them with 1-to-1 technology and teaching them to use it effectively.

As part of this initiative, we spent over 2.5 million dollars renovating spaces, buying furniture and technology, and training teachers and leaders. As a result, our staff is now working collaboratively to design authentic projects. We've moved our teacher desks into one of two "Bullpens" where teachers meet between classes and during prep. We integrate courses whenever integration makes sense. Our students take classes like "GeoDesign," "BioLit," "American Studies," and "Civic Reasoning." Each of these classes have two teachers and more time to learn from their work. We are doing a lot of things differently. And better.

To put things back into perspective, we have two groups of students dual enrolling this year: seniors and juniors. Both were educated by the same teachers in the same school. The juniors are part of our New Tech initiative. The seniors are not. The circumstances are begging for further analysis!

To start, let me describe the students. Last semester, we had 67 students dual enroll: thirty-nine juniors and twenty-eight seniors. Both groups represent what we would consider our "top third" performers (more juniors dual enrolled because their class size was larger). The average high school GPA for the groups were close: 3.39 and 3.32 respectively.

They were also demographically similar. Both groups had a few more boys than girls. They represented only a third of our free and reduced lunch population (only 18% of dual enrolled students vs 55% total high school enrollment). They were racially similar, 99% white, which is consistent with our district and community makeup.

The one demographic difference that stands out to me is the obvious one: seniors are, on average, one year older than juniors. They also have one more year of high school experience and are one year closer to entering college full-time. While I cannot say that this information is statistically significant, after working in high schools for the past ten years, it feels anecdotally significant.

In college, they also performed similarly when looking at the average. Seniors passed 96% of college classes with a GPA of 3.01. Juniors passed 92% of college classes with a GPA of 2.90. Failure was experienced by just three students, one senior and two juniors.

One other comparison that seems notable is that both juniors and seniors took similar courses in college with one potentially significant exception: being farther ahead in curriculum, more seniors took advanced math than juniors (46% vs 13% respectively).

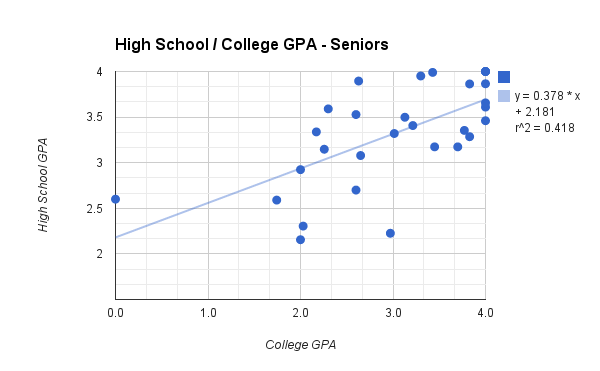

Where performance differences become noticeable is in the way individual GPA distributes across students. The graphs below demonstrate that difference by overlapping the distribution of high school and college GPAs for each group independently.